The True Crime

May 26, 2023

Before the 1995 spectacle People versus OJ Simpson was tagged as the trial of the 20th century, another trial held the title. It was the 1935 trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann for the kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh, Jr., the nearly two-year-old son of the world-famous aviator Charles Lindbergh. The recent anniversary of the child’s body’s discovery sent me down a winding path where I discovered the crime of the 21st century.

The case has woven its way throughout my life and rests at the intersection of two streets where I’ve hung out the most. History and Crime. As a young boy, one of the first books my grandfather gave me was Kidnap: The Story of the Lindbergh Case, written by George Waller and published in 1961. In college, pursuing a degree in criminal justice, one of my lead professors was Jim Fisher, a former FBI agent, private investigator, lawyer, and writer, and one of the most engaging teachers and storytellers I have ever met. In 1987, a few years after I graduated, he published The Lindbergh Case: A Story of Two Lives, the first book on the kidnapping to include a thorough analysis of the NJ State Police files. He wrote a follow-up book The Ghosts of Hopewell: Setting the Record Straight in the Lindbergh Case, which debunked many theories on the crime that have at their core the innocence of Hauptmann or claims he did not act alone. Eleven years ago, I performed in a community theatre production of Hauptmann, a play about the case. I’ve continued to read the occasional book or article and watch a documentary or two.

Somebody took the boy from his bed on March 1, 1932. Left behind were a ransom note and a homemade ladder used by the kidnapper to climb in and out of a window. In the following weeks, the kidnapper sent multiple letters, and eventually, Lindbergh paid $50,000 in exchange for information on the boy's location. The information was a ruse. On May 12, the badly decomposed body of Charles Lindbergh, Jr was discovered about four and a half miles away from the family home. He died the night of his abduction and was left there.

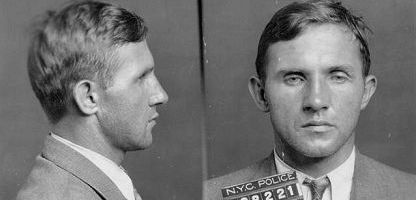

The investigation continued, but it wasn't until 1934 that police arrested Hauptmann after he passed some of the ransom money. He was tried the following year and sentenced to death. Some of the extensive evidence against him included the testimony of eight handwriting experts who identified the ransom notes as written by Hauptmann, a piece of the kidnapper's ladder made from a piece of wood taken from Hauptmann's attic, and the $14,000 of ransom money in his possession. The balance of the cash Hauptmann invested in the stock market and spent on a lavish lifestyle, which did not align with his years of unemployment. He lost on appeal, and on April 3, 1936, Bruno Richard Hauptmann died in the electric chair.

The newsletter prompted me to dig around online, rewatch two documentaries, a 1989 New Jersey public television production, and a more recent 2013 PBS episode of Nova, and read through both of Fisher’s books and Waller's.

The evidence clearly implicates Hauptmann as the kidnapper and killer. Although there are theories he didn't act alone or wasn’t involved at all, and some others of a “Bigfoot landed a flying saucer in my backyard” variety, there has never been any solid evidence to support them.

Out of curiosity, I looked to see if Hollywood had produced any dramas about the crime. In today's world, you can't seem to have a crime or tragedy without a "Based on a true story" retelling. I found two. A 1976 made-for-television movie, The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case, and a 1996 HBO production, Crime of the Century. Both are available on YouTube.

The 1976 movie was a relatively straightforward presentation of the case with the usual dramatizations and conjecture included for entertainment value. It starred Anthony Hopkins as Hauptmann. While watching it I couldn’t help imagining Hauptmann telling his police interrogators that he once ate a census taker’s liver. The HBO movie was a crime of its own, perpetrated on the reputation of the police and prosecutors. It presented a fictionalized case that Hauptmann was an unwitting recipient of the ransom cash, and the New Jersey State Police, the New York City Police, and the prosecutor all conspired to create false evidence against him, and the only man who wanted the truth, the governor of New Jersey, was silenced under threats of his political death.

While watching this movie, I repeatedly yelled at the screen. Things like "that's not right," "oh, come on," and "that never happened" strung together with words more appropriate for watching a Pittsburgh Steelers/Baltimore Ravens football game.

I also searched true crime podcasts and video streaming channels, which in recent years have exploded in number. I found an episode on a proclaimed crime expert's YouTube channel with nearly 9,000 views, so I watched it. If I shouted angrily at the HBO movie, I sat mute with disbelief for all of this stream’s 56 minutes. The expert included the HBO movie as part of their very limited research and claimed it was well done. But according to them, Fisher’s 1987 book was too long and contained too much information. Because when you’re researching a murder and a man’s subsequent execution for it, you don’t want to spend time reading information when you could be watching a nearly 30-year-old fictionalized version of the event.

Before this expert began their disjointed discourse that plays loose with the facts and makes broad unfounded assumptions, they shook their digital paper cup and pitched for donations, subscriptions, and book purchases through their Amazon affiliate page. At the episode’s conclusion, they concluded Hoffman was involved, but he couldn't have acted alone and then identified who they believe assisted him. In the comments section of the episode, viewers thanked them for clearing up the case and praised them for their research and analysis. I wouldn’t be surprised if many of them went and wallowed in the HBO movie slop.

During my digging, I found a recent news article about the case. A woman identified as a freelance researcher is working with a screenwriter and film producer to create what she described as the “definitive documentary” on the crime. Late last year, she sued the state of New Jersey in Superior Court to gain access to the envelopes, letters, and ladder so they could be subjected to DNA analysis, which wasn’t available at the time of the original investigation and trial. It was dismissed by a judge who said, "The state's open records law is not the vehicle by which a citizen can march up to a museum and demand that the custodians of historical artifacts and documents surrender the state's treasures for analysis, alteration, and destruction." I didn’t find a record of an appeal.

After my performance in Hauptmann, Chris bought me the actual front page of the April 4, 1936 edition of The Boston Herald, which declares in a two-line bolded headline:

Bruno Hauptmann Executed

Dies Without Saying Word

The word the world wanted and expected to hear was a confession. Even after his conviction, failed appeals, and a promise from the governor to commute his sentence to life if he confessed, Hauptmann maintained his innocence.

For grins, I took ChatGPT for a ride on the subject. I'm sure it won't be too long before someone applies this technology to true crime if they haven't already. I asked if Hauptmann had an accomplice in the Lindbergh kidnapping and murder. The response (the emphasis is mine) read:

“While there have been theories and speculations about the possibility of an accomplice in the Lindbergh kidnapping, Bruno Richard Hauptmann consistently maintained that he acted alone in the crime. There was no concrete evidence found indicating that he had an accomplice, and no one else was ever charged or convicted in connection with the kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh Jr.”

There’s the intelligence taking over our world.

In an interview when The Lindbergh Case was published, the reporter asked Fisher why some writers purported the verdict was incorrect and Hauptman was innocent. His answer could easily apply to true crime books today. He said, "They did it for the same reason that Hauptmann stole a child – to make money. If they truly believe what they wrote, they are either charlatans or fools. They are weaving the kind of stories found in supermarket tabloids."

Fisher said he didn't write the book to upset Anna Hauptmann, who made it her life's mission to try and have the case reopened, and her husband exonerated. "But I can't change history to save her feelings."

The continued questioning of Hauptmann's guilt and efforts to re-investigate and re-try the case is an example of the true crime in true crime. The seemingly endless number of podcasts, documentaries, docudramas, books, and articles on the topic. Some are thorough well-sourced searches for the truth, but others are crime stories manipulated to deliver someone's political or social message. And still others are weak attempts to cash in on the genre's popularity. And like junkies, many true crime addicts aren't discerning where they go to ease their craving and consume whatever's available without bothering to determine if its facts are contaminated or its information diluted. Too many people want to change history to put some change in their pocket. And too many people are willing to give it to them.

The crime of this century is true crime itself.

Like what you read?

Subscribe to my mailing list and get notifications to your inbox when my next blog post goes live.

Contact Us

More By Joe