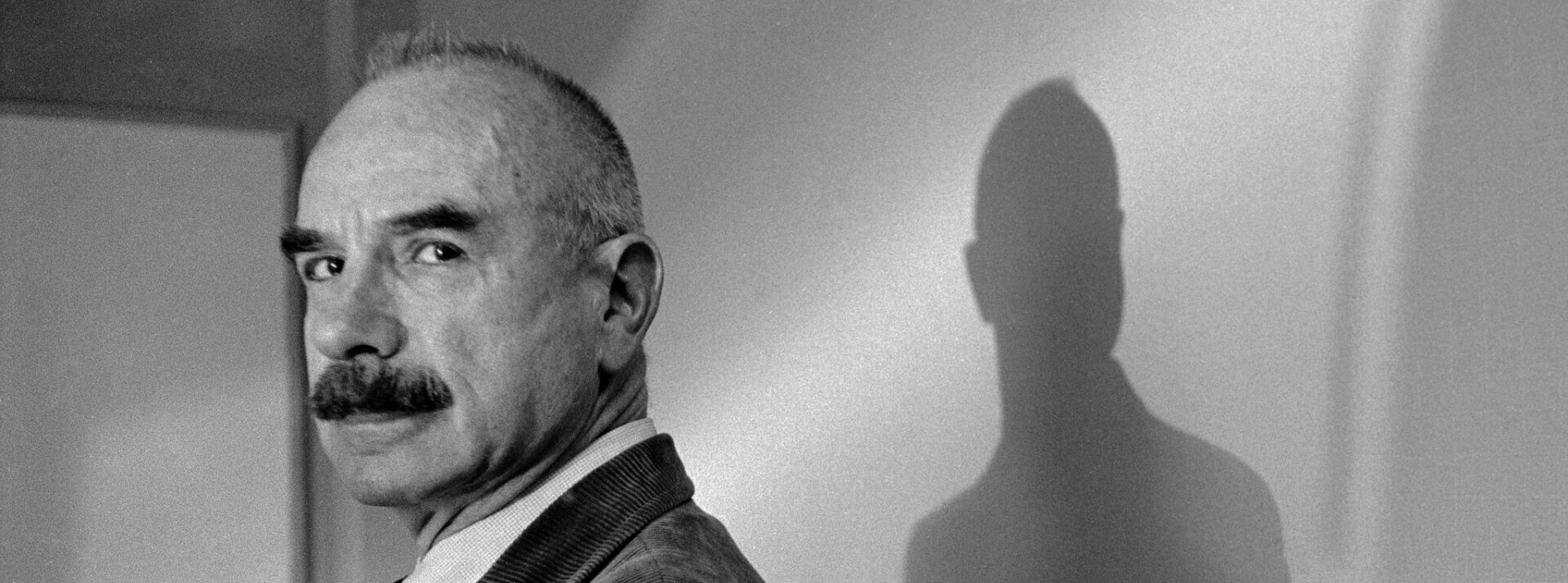

Liddy's Lessons

April 9, 2021

Photo Credit: Paul Hosefros/The New York Times

Liddy, age 90, died recently. His obituary read like a mixture of pulp fiction, dark comedy, and political satire. But his life was all too real. As a young boy, he overcame a fear of rats by cooking and eating one. He burned the word Watergate into our collective consciousness in his inept planning and execution of not one but two burglaries on the offices of the Democratic National Committee. Afterward, he offered to stand on a corner and let someone shoot him if it would save the presidency, played villains on television, and was himself portrayed in a television movie.

On the surface, his resume reads like a list of jobs that even just one would fulfill the dreams of millions. United States Marine, FBI agent, lawyer, county prosecutor, special assistant in the United States Department of the Treasury, White House aide, general counsel for the committee to re-elect the president, author, actor, college lecturer, and nationally broadcast radio talk show host. Underneath are cloak and dagger tales involving the CIA, Cuban freedom fighters, black bag jobs, burglaries, wiretaps, disguises, code names, aliases, and unexecuted plans that included kidnapping and blackmail. At the bottom are four and a half years spent in prison and advising his radio listeners to aim for the heads of agents of the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms because they wear bulletproof vests.

I help college students learn history and leadership by studying historical figures, most recently presidents John F. Kennedy and Dwight Eisenhower. Sometimes though, the leadership lessons offered through history come from unlikely sources, like G. Gordon Liddy. His life was shrouded in conspiracies. But tangled within them are a few lessons for leaders.

First, don't pass along your problems. Leaders sometimes solve a performance problem by convincing the poor performer they might be a better fit somewhere else in the company. Then they convince someone to take them. Sources within the FBI said Liddy was forced out for incompetence. His personnel file said otherwise and allowed Liddy to get a job as a prosecutor and eventually land a Treasury Department position. Treasury had their fill of Liddy and passed him along to the White House. It’s here, with the help of others, he turned an assignment to quietly secure information to discredit Daniel Ellsberg (who leaked confidential government documents to the public) into a break-in of Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office staged to look like a frantic search for drugs. Instead of finding himself behind bars or banished from Washington, Liddy ended up as general counsel for the president’s re-election campaign. It’s here that Liddy and some of the same bunglers from the Ellsberg fiasco gave us the Watergate burglary, which in turn led to the resignation of President Nixon, and decades of books, documentaries, movies, and television shows trying to make sense of it all. If Liddy's FBI file had documented his inadequacies, would he have made it to Treasury? Or if Treasury had shown him the door to the street instead of the White House, or his bosses at the White House tossed him over the East Gate, would the Pentagon Papers have been shelved, and Watergate remembered as just overpriced real estate?

Spending time defusing employees who are ticking time bombs or marching them to the nearest exit saves the company from an almost inevitable explosion and the destruction of productivity, profits, and reputation.

The second lesson is to be precise in your communications. Not everyone can interpret broad directions or differentiate between sarcasm and actual instruction. One of Liddy’s bosses at the re-election committee, frustrated by Washington columnist Jack Anderson, made an offhand comment within earshot of Liddy that they would all be better off if Jack were dead. If Liddy didn’t share what he took as an order to assassinate the reporter with another committee staffer, who sounded the alarm, Anderson might have faced the ultimate deadline. Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office's ransacking and the bugging of Democratic National Headquarters were both consequences of vague instructions and broad demands for results. Making an offhand remark about your dislike for someone is unlikely to lead to a colleague's assassination, and ambiguous instructions probably won't cause the CEO’s resignation. But it could lead to problems that clear communications and direction could have avoided.

The last Liddy lesson is for everyone, not just leaders. His obituary is a telling narrative. The story of a man who, although sometimes misdirected and of questionable judgment, was no stranger to adversity, failure, and public scrutiny. A story that could have ended many times with Gordon’s fading into the cultural woodwork. Instead, he marched forward. Disappointments, mistakes, and failures aren’t street corners where we stand to be silenced. They’re hot flames held against our lives that we have to learn to tolerate with will, courage, and conviction.

History has primarily cast G. Gordon Liddy as a slightly crazed criminal conspirator and convict. But with some effort, even the darkest figures can enlighten us. In Liddy's case, the work requires a set of lock picks and a prybar.

Like what you read?

Subscribe to my mailing list and get notifications to your inbox when my next blog post goes live.

Contact Us

More By Joe